Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

Personal Note from J.B.

I’m indebted to Pat Sheldon for putting me on to one of the best 5-minute videos I’ve seen on the Internet. Of course it helps that it’s funny, features a true hero, and concerns one of my favorite topics—the SR-71 Blackbird, that fabulous titanium airplane from the 1960s.

The SR-71 was developed by Kelly Johnson at Lockheed’s fantastic “Skunk Works.” (I once witnessed one of the ‘Birds’ take off from Kirtland Air Base in Albuquerque. It was a fabulous sight!) I hope you enjoy this story . . . and the video, narrated by Major Brian Shul.

I read lots, and Leonardo da Vinci is one of my favorite artists, so I bought Walter Isaacson’s new biography (600 pages, counting back matter!).

I seldom do book reviews, but “The Muse Inside Leonardo” reviews the new book by Isaacson, one of my favorite writers. Maybe it’s not really a review, because I concentrate on Isaacson’s misstep rather than on an assessment of the whole. You can judge. Let me know what you think.

A blonde joke takes center stage for “Wisdom With a Smile.” Need I say more?

The third story below is all about my 35-year relationship with New York, and the art organization there that is among the oldest in the United States. The Salmagundi is housed in a truly outstanding brownstone on Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. If you ever have the chance, try to visit it!

Lastly, and perhaps too exotic except for the writers tuning in, is “’Show Don’t Tell’: How I See It,” which delves into what is perhaps the most-often misunderstood advice given to writers, journalists as well as novelists.

In case you missed it, take about three minutes and enjoy our video book trailer on the home page!

Best wishes to all of you in this new year of 2018!

The King of Speed Lives

In one of the most entertaining 5-minute videos on the internet, Major Brian Shul relates an amusing story of one of his missions piloting an SR-71. (If you’re unfamiliar with the SR-71, just know that back in 1990 this aircraft was flown from L.A. to New York City in 67 minutes—yes, just over one hour!)

Near the end of the Vietnam war, having flown a U.S. Air Force jet on over 200 missions, Shul was shot down, thought to be near death, yet recovered. His story of the SR-71 training mission over the U.S. mainland had particular relevance for me because it involved an unnamed Navy pilot, reminding me of my U.S. Navy days when I helped train cadets in navigation.

As Shul’s story begins, he’s at the controls of the two-cockpit version of the Blackbird, with “Walter” in the Recon officer’s cockpit behind—this being what the flyers call the Blackbird’s “family model”—on the mission at 89,000 feet over the U.S. Southwest.

Walter is monitoring five radios from this altitude over Tucson, where they can clearly see downtown L.A. They’re in airspace that L.A. Center controls, although at this altitude they’re above controlled airspace. (L.A. Center is short for Los Angeles Air Route Traffic Control Center in Palmdale, which controls 177,000 square miles of airspace in California, Utah, Nevada, and Arizona.)

While listening to chatter on L.A. Center’s radio frequency, Shul says, “It’s really cool the way they—the controllers—talk, makes you feel important, as a pilot.” He shortly notes that some guy flying a Cessna quizzes L.A. Center for his ground speed. Although Shul knows that the ground controller would like to say, “Who cares? Get off the freq,” the controller replies, in a calm, cool voice, “Cessna, we show you at nine zero knots, on the ground.”

L.A. Center also has a twin Beech on their scope. Its pilot, perhaps to show up the lazy speed of the Cessna, requests a speed check. Again calmly, as though giving Air Force One a courtesy check, L.A. Center says, “Twin Beech, we show you at one-twenty. One two zero knots on the ground.”

Immediately, a Navy F-18, high over the Rockies in a move to show everybody that he’s “the meanest, badest, fastest military jet in the Valley today,” requests a speed check. This despite, as Shul notes, the million-dollar Navy F-18 has a “heads up” display of ground speed “right there in the cockpit.”

Again, however, L.A. Center cooly replies, “Dusty five two, we show you at six-twenty. Six two zero knots across the ground.”

To Shul’s surprise, he then hears a click from the SR-71’s rear cockpit where Walter is in charge. “Oh, no,” Shul says, “it’s the Navy, and the Navy must die now.”

Sure enough, Walter’s voice crackles over the radio, “L.A. Center, Aspen three zero. Do you have a ground-speed readout for us?”

In the legendary calm voice of L.A. Center’s controllers came the reply, “Aspen three zero, we show you at one-thousand-nine-hundred-ninety-two knots across the ground.”

Shul says he quickly realized a crew had been formed with Walter as the cool-voiced reply issued from the SR-71’s rear cockpit: “L.A. Center, we show a little closer to two-thousand.”

The Navy had thus been flamed and the ‘King of Speed’ was henceforth affirmed.

The Muse Inside Leonardo?

My admiration for the writing of Walter Isaacson owes much to 2009’s American Sketches, (Simon & Schuster, New York, NY) in which he admits to “the joys of unearthing tales about interesting and creative people.” From there, it’s not hard to imagine how I looked eagerly forward to Isaacson’s Leonardo da Vinci (Simon & Schuster, New York, NY, 2017). Alas, my enjoyment of this book was limited.

As David McCullough announces on the dust jacket, “Isaacson is…a true scholar…[a] most engaging, informed and insightful guide…” and Isaacson quickly sets the reader straight: “Leonardo da Vinci is sometimes incorrectly called ‘da Vinci’”—a reference to his hometown of Vinci.

The research for this biography of Leonardo was clearly exhaustive. Isaacson took the more than 7,200 pages of Leonardo’s notes as the basis for the book. It also benefitted from numerous art experts and researchers who gave Isaacson private access to historic documents and artworks. These included Luke Syson of New York’s Metropolitan, Vincent Delieuvin and Ina Giscard d’Estaing of the Louvre, David Aloan Brown of the National in Washington, Valeria Poletto of Venice’s Gallerie dell’Accademia, Pietro Marani of Politecnico di Milano, Alberto Rocca of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan and Jacqueline Thalmann of Christ Church, Oxford.

Unfortunately, the book’s illustrations of Leonardo’s work are poorly executed and often too small. I found this especially frustrating in trying to follow discussions of Leonardo’s drawings of machines. Small details are often essential to understanding how a machine functioned or was intentioned to function, yet such small details were often impossible to discern because of the illustrations’ small dimensions.

In addition, I found Isaacson’s detailed discussions of Leonardo’s drawings occasionally sloppy. For example, what is meant by “cross-hatch shadings” is that the lines that form the shading cross (intersect). Yet the author fails to distinguish between “cross-hatch shadings” and the simple “hatchings” that Leonardo executed with his left hand. Lines that do not intersect—hatchings—were frequently Leonardo’s preferred and recognized shading method. They became a kind of ‘signature’ of his drawing technique.

Early in the book we learn of Leonardo’s illegitimate birth, his homosexuality, his obsessive curiosity on diverse subjects and (over and over) his inability to complete works he had agreed to complete. As information that aids a reader’s insight into Leonardo’s personality, this is all fair enough.

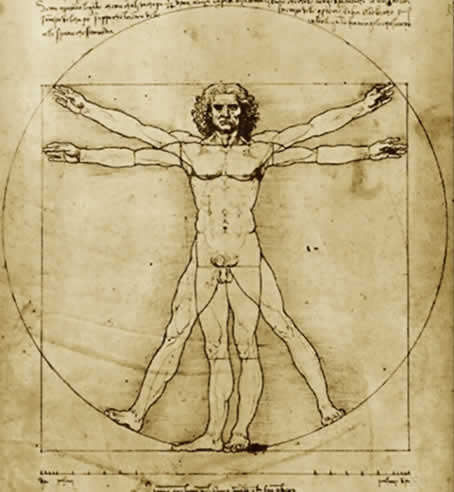

A third of the way into the almost 500-plus pages, Isaacson discusses what is probably Leonardo’s most well-known drawing, “The Proportions of the Human Figure (after Vitruvius),” or more simply Vitruvian Man. He notes that the drawing is “meticulously done…[its] lines are not sketchy and tentative.” Acknowledging that Leonardo might have left the drawing more diagrammatic, he writes, “Instead, he used delicate lines and careful shading to create a body of remarkable and unnecessary beauty.” While these affirmations are appropriate, I was most disappointed in the author’s final paragraph on this drawing:

“Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man embodies a moment when art and science combined to allow mortal minds to probe timeless questions about who we are and how we fit into the grand order of the universe. It also…celebrates the dignity, value, and rational agency of humans as individuals. Inside the square and the circle we can see…the essence of ourselves, standing naked at the intersection of the earthly and the cosmic.” (p. 157)

I have no trouble praising many of Leonardo’s drawings or the Vitruvian Man in particular, a brilliant feat of pictorial communication. What Vitruvian Man does not show or even suggest is a probing of “timeless questions about who we are and how we fit into the grand order of the universe.” Nor do I see, inside “the square and the circle” anything like ourselves, standing at the intersection of the earthly and the cosmic. Such philosophical musings are not subject to images on paper.

Walter Isaacson is to be thanked for his earnest contribution to Leonardo literature. Readers should however be prepared to disregard a few errors and especially, the unneeded and unwarranted characterization of Leonardo’s drawing as a foray into grand philosophy.

Wisdom with a Smile

I like blonde jokes. Here’s a favorite:

A brunette, redhead and a blonde were discussing the greatest modern invention.

The brunette said, “It just has to be the telephone. With these marvels we can communicate with each other wherever we are in the world.”

“No,” the redhead said. “It has to be the airplane. Thanks to flying, we can travel anywhere in the world in a matter of hours.”

“I disagree with both of you,” the blonde said. “For me, the greatest modern invention is the thermos flask. Think about it. If you want something hot, you put hot stuff in it. If you want something cold, you put cold stuff in it.”

The redhead looked puzzled. “Yeah, so?” the brunette asked.

“Well,” the blonde said, “how does it know?”

None of us are truly “experts” when it comes to computers. Although rare, computer experts do exist. “The trouble with you,” his wife said as she scratched his back, “is that you eat, sleep and breathe computers.”

“No,” the husband said, “that’s just not true. Scroll down a little . . .”

Making it in New York

Even if you weren’t around in the 1950s, you’ve probably heard Frank Sinatra’s line from the song New York, New York: “If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere/It’s up to you, New York, New York.” Although I’ve never lived in New York and have only visited there a few times, you’ll forgive if I claim to have “made it there.”

It happened thirty-five years ago.

The tragedy of 9/11, Mayors Giuliani, Dinkins and Koch, the Zodiak killer, the reopened Guggenheim, events large and small have occupied New York over the intervening years. More modestly, thirty-five years ago I was elected an artist-member of the famed Salmagundi Club. This followed my receipt of the jury’s Print Award in the Club’s 5th Annual Open Non-member Exhibit.

Founded in 1871, the Salmagundi Club is almost the oldest art organization in the United States. It’s housed in an historic brownstone mansion at 47 Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. Members enjoy socializing in the Club’s facilities, including its three art galleries, a library, an elegant period double-parlor (photo), a restaurant and a bar.

The Club’s art collection spans its 147 year history. Past members include important American artists such as Thomas Moran, William Merritt Chase, N.C. Wyeth and Childe Hassam.

The Club originated in 1871 as a sketch class in Jonathan Scott Hartley's studio. A hundred years ago the Club purchased this mid-nineteenth century brownstone house as a permanent home. It is now a New York Landmark.

Current membership numbers nearly 850, including both artists and patrons. The Club sponsors programs including art classes, exhibitions, painting demonstrations, as well as hosting book parties, music and author events. Artist-members may exhibit their work in four to six exhibitions a year. Artist-members’ profiles, with art examples, are on the Club’s website.

Beginning with my first jury-chosen entry in an art exhibit (a watercolor in the 7th Annual Northern Indiana Art Salon) I strove to prove myself a serious artist. As it turned out, my paintings, etchings or drawings were selected by juries, or included by invitation, in U.S. art exhibitions at least once each year for the next thirty-seven years.

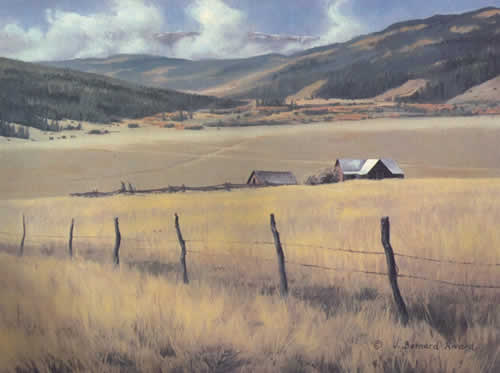

Reproduced here is an example of my New Mexico landscape paintings. The 18”x24” oil, “Morning Freshness” was reproduced in color on the 1979 calendar published by New Mexico Magazine.

During the last quarter century my novels, short stories and non-fiction articles, some of which include my artwork as illustrations, have been published in both paper and electronic forms. Music composed by me has also been performed by both professional and amateur musicians during this period.

There’s little doubt in my mind that I’ve been exceedingly fortunate in achieving success in creative endeavors over these many years. Nevertheless, I’d be hard-pressed to single out an honor greater than being elected an artist-member of the Salmagundi Club of New York City, thirty-five years ago.“Show Don’t Tell”: How I See It

We writers are often told how to write. Enter “advice for writers” into Google and you’ll get at least a hundred-million results. One of the most often-repeated instructions is “show, don’t tell.” This aphorism can mean different things to different writers. Despite the word “show,” it does not suggest you should write showy, in an ostentatious manner.

One expert said it means, “Don’t lecture your reader.”

For what it’s worth, I’ll try to explain my interpretation of this adage, an approach that might be labeled, “engage, don’t explain.”

Sol Stein, editor, publisher and author of nine novels, said the job of the novelist is “providing an extraordinary experience for the reader, who should be oblivious to the fact that he is seeing words on paper.” Stein’s precept is a tall order.

Implementing an approach which provides an extraordinary experience requires dedication to fueling the reader’s mind and emotions. As the late E. L. Doctorow made clear, “The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.”

The electricity of written drama, where the reader is fully engaged by the actions and speech of the players, can provide the experience Stein writes of.

I might write, “It had been terrible, watching her son help Red with the body. Iris went into the bathroom where Nick could not see the white fear gripping her. She hoped splashing cold water onto her face would help her cope.”

This exposition, in addition to defining Iris’s action of entering the bathroom, explains what she saw, that she found it terrible, that she now feels fear, that she wishes Nick not to observe that fear, and that splashing cold water onto her face might help her manage her emotions. But explaining what a character in a story does, sees, and feels fails to induce the reader to become deeply involved in her situation.

What follows is what I wrote in my novel Illusions of Magic: “She stood, stepped to the basin, turned on the cold water and let it fill her cupped hands. She splashed the water on her face, grasped the hand towel and wiped. As the towel slipped from her face, she caught a glimpse of herself in the mirror. “Oh,” she said, closing her eyes to the image.”

Here I am dramatizing. The four sentences don’t mention Iris’s fear. They don’t explain why she acts as she does. Rather, they allow us to observe as she performs simple actions—until she inserts an unusual action: avoiding the appearance of her own face. If, in the context of the rest of the story, the reader senses Iris’s fear, then the intended effect has been achieved.

Casting a story as drama is to me the way to engage the reader. As the drama unfolds, the reader gradually learns more about the characters, their attitudes, likes and dislikes, perhaps their fears and their hopes, even their unconscious impulses. This is much the same process we experience in real life, where we observe those around us, and, over time, grow to know them more and more intimately.

Involving the reader in the drama of the story is, like living, a more natural way to prompt commitment and empathy. To me, “engage, don’t explain,” is the best way to evoke readers’ extraordinary experience while keeping them oblivious of the fact that the story consists of mere “words on paper.”

Thanks

Thanks for all those reading and reviewing Illusions of Magic.

A tip of the hat to those who take time out of their busy day to read my blog.

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!