Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

October 2021

In this Issue:

Personal Note from J.B.

My writing of the novel-in-progress titled Dead Heat to Destiny (see “A New Project” in the March 2021 blog), begun at the first of 2021, continues. Although the progress is steady, it is painfully slow.

Although the story is fictitious, I want readers to rely on it. This means that the world inhabited by my characters must be one that a reader feels actually existed in the past. Building this world requires research that enhances its authenticity.

Authenticity can be thought of as the quality, or condition, of being trustworthy, or genuine. Gaining the elusive authenticity, I find, entails much research, as described below in “World Building.” Unfortunately, the effort also contributes to the slowness in completing the book.

One of the joys of researching the past, however, is discovering obscure events or developments that either add to one’s creative efforts or contribute to fascinating but extraneous writing. The latter describes the nature of my main entry below, “Kapitän Feldt’s Forgotten Attack on the United States,” a little known, or forgotten, aspect of WWI in the United States.

I hope you enjoy my blog. Please take time to comment, about the website, the blog, or other topic. (Be sure to tell me who it’s from.) Simply send an email to feedback@illusionsofmagic.com.

World Building

World-building is required for each major character in a novel, as well as for the major supporting characters. World-building requires more than ascertaining physical surroundings. The nature of society, the culture, and each specific setting (garments worn, businesses patronized) for the character must also be determined to some level of accuracy. The accuracy needed and achieved depends on the strength of the writer’s desire for authenticity.

My novel-in-progress’s subtitle is “Three Lives in World War One.” The three major characters who fulfill that billing inhabit different countries during the first years of the story. Their ages also differ. These aspects increase the amount of research required.

By the quarter-point of the novel, two of the major characters are in Paris during the years before WWI. This era, often known as Belle Epoque (Beautiful Period) was a time of rapid artistic, economic, and technological change. For example, in 1903, most Paris taxicabs are horse-drawn; by 1906, there are 417 registered motor-powered taxis; by 1908, there are 1,465 motorcar taxis registered. One’s writing must reflect such quickly-changing conditions.

Adrien Boch, the major female protagonist, works in women’s fashion in Paris at this time—producing the necessity for probing the exciting developments in haute couture that changed women’s costumes drastically, and forever.

Later, the two major male characters become military officers for nations which participate in World War I on opposing sides. Needless to say, the two nations disagree on many levels and ultimately clash. The political and military opposition affects these men in major ways.

The major supporting character in the novel is a spy. Although his involvement does not rise to the level of the major characters, the research into his accomplishments has required a large amount of research into obscure niches of the historical record.

This world building contributes to slowing the completion of the novel. The slowness results from something I’ll call the ‘Research Ratio,’: the time spent writing divided by the time spent on research. The smaller this number, the slower the writing. For example, if the Research Ration is 0.5, twice as much time is spent researching as writing. There are times when my Research Ratio has fallen below 0.3.

There are two contributors to the amount of research required: the degree of authenticity desired and the difficulties encountered in performing the research.

The degree of authenticity desired is subjective, as is suggested above in my Personal Note.

On the other hand, the difficulties in accomplishing the research depend greatly upon the writer’s resources, including the world’s largest library—the Internet—as well as the obscurity of the sought-after fact and the writer’s ingenuity in discovering pertinent sources. Occasionally, the fact or development needed may not exist in the historical record—a most distressing situation.

Kapitän Feldt’s Forgotten Attack on the United States

The message received at the Chatham Naval Air Station the morning of July 21, 1918 was crisp:

“Submarine sighted. Tug and three barges being fired on, and one is sinking three miles off Coast Guard Station 40.”

Station 40 was on Nauset Beach, southeast of Boston.

It took Eric Lingard, a Navy Ensign, some minutes to gather a crew to man the Curtiss HS1L flying boat that would respond. Once copilot Ed Shields, also an Ensign, was seated beside him with motor running, only a bombardier was needed. Chief Special Mechanic Edward Howard waded out, climbed into the circular station in the prow of the flying boat, and Lingard increased the craft’s throttle.

The roar of the Liberty motor was deafening, but the biplane’s progress across the water was less impressive. Its two fabric-covered wings fluttered as the craft plowed through the chop. The wings were held about eight feet apart by struts and wires, with the lower wing, attached at the top of the hull-shaped fuselage, catching an occasional dash of seawater.

Lack of a windscreen gave Lingard an unobstructed view ahead because the big motor and its radiator were located behind and above the cockpit. This design permitted the pusher propeller to whirl in a huge arc behind the upper wing. Taking off into the wind, however, often turned soggy, as spray from the prow flew unimpeded into the aviators’ faces.

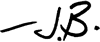

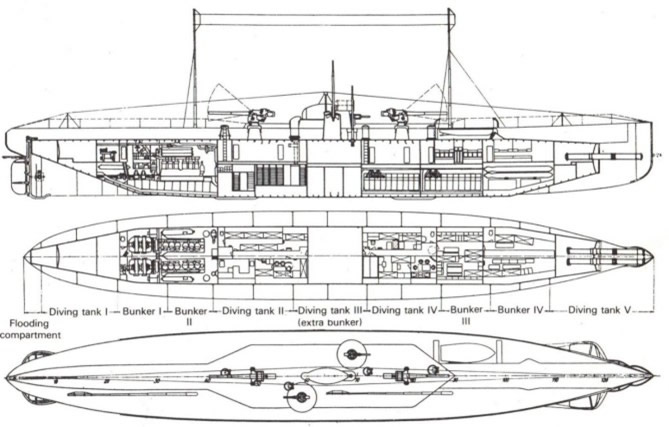

Lingard finally lifted the aeroplane from the water. Upon gaining a few hundred feet above the sea, the aviators had an initial view of the unfolding drama off Nauset Beach: The gray hulk of a surfaced submarine, at 213 feet the largest of the German U-boat fleet; the steam tugboat Perth Amboy, about half the sub’s length; and the tug’s tow—four three-masted cargo barges strung out behind the tug like baubles on a necklace.

But U-156 Kapitän Richard Feldt was not attending a soiree, he was commanding the crews firing the four big guns on its deck. Their target, hundreds of yards toward shore, was the tug and its tow. With thundering regularity, orange flame belched from the sub’s guns. And with nearly equal regularity, the fired shells raised only geysers of seawater, or blasted giant craters into the sand of Nauset Beach. Whether by chance or intention, some of the shells scored—at least one of the barges was sinking, and holes appeared in the tall funnel of Perth Amboy.

As the crew of the flying boat arrived in the vicinity, a shell hit the tug’s pilothouse. The aviators initially saw only a flash, but a tangle of wreckage was visible when the smoke cleared.

Although the flying boat was not yet at the recommended safe bombing altitude, Lingard shouted toward Chief Howard in the bombardier’s station, alerting him that he planned a bomb run on U-156. The aeroplane carried only a single Mark IV bomb, and Lingard wanted success. He aligned the aeroplane and Howard tripped the bomb release. From only 800 feet of height, Howard thought, the bomb might score a direct hit.

Unfortunately, the bomb did not release from its rack. The three aviators cursed in disbelief as the flying boat passed over the busy gunners of U-156.

Lingard banked, and began a wide turn out to sea and beyond the submarine. He retarded the throttle, descended lower, and again approached the target. He alerted Howard of a second bomb run. Again, Lingard aligned the craft and Howard tripped the bomb release. Again, the bomb failed to release.

Below, Kapitän Feldt saw he was under attack from the air. He commanded the crews of the two smaller-caliber guns close to the conning tower to redirect their fire from the tug and tow to the low-flying biplane.

Totally frustrated, Chief Howard realized the bomb release mechanism was inoperable. As Lingard again circled away from the target, Howard turned, emerged from his seat and crawled rearward along the fuselage. At its juncture with the lower wing, he grasped the struts between the wings to steady himself. Both pilots watched fearfully as Howard, his flying suit flapping vigorously, edged out toward the underwing bomb rack.

An orange flame spouted from one of the newly-aimed deck guns on U-156, but Lingard completed his circle. He straightened and aimed for the submarine. The shell fired at the aeroplane missed.

With one hand gripping a strut, Howard reached for the release mechanism and, at the estimated moment, released the bomb. It splashed into the sea near the submarine, but did not explode. The aviators cursed.

As quickly as he dared, Howard edged back toward the fuselage.

More orange flames issued from the guns aimed at the flyers. Fortunately, all the shots went awry. As Howard athletically reclaimed his station in the craft’s nose, Lingard increased power to gain more height and distance from the submarine’s gunners.

On the Perth Amboy below, several of the crewmen were injured by the shelling. The boat’s skipper, James Tapley, realized his tugboat was a slow and easy target. He reluctantly issued the order to abandon ship.

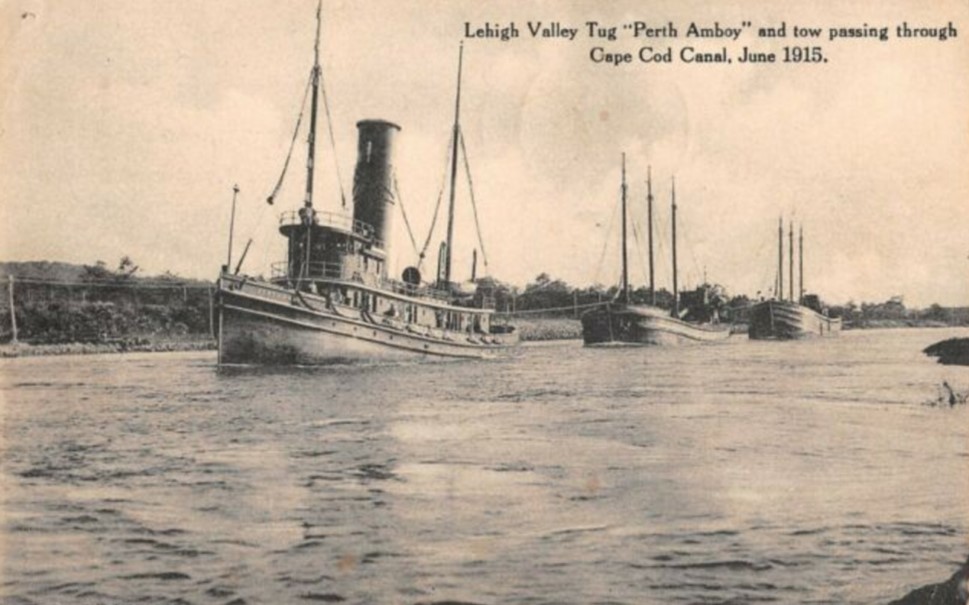

It was now after eleven a.m. At Chatham Naval Air Station, a biplane piloted by U.S. Coast Guard Captain Philip Eaton touched down. Eaton, the commander of the Station, had received his pilot training in the U.S. Navy. He was out searching for a disappeared blimp during the submarine attack. He pulled to a stop and was briefed on the attack and Lingard’s mission. Less than fifteen minutes later, he took off in an armed Curtiss R-9 float plane.

In minutes, Lingard, circling at a safe altitude above the battle, saw Eaton’s plane approach—“the prettiest sight I ever hoped to see.”

On the conning tower, Kapitän Feldt also saw the approach of Eaton’s plane. It was flying low, directly at U-156. Feldt’s smaller-caliber guns now aimed at the oncoming biplane and fired, but failed to hit the R-9 float plane. Eaton swooped low to about 500 feet above the water and released his payload. As he passed over the submarine, he saw that the bomb would miss the vessel but land close enough to inflict damage. He braced for an explosion, but saw only a splash. Again, the Mark IV bomb failed to detonate.

Angry at the bomb’s failure to explode, Eaton circled out to sea, returned, and again took aim at U-156. Again the gunners fired at him, and again they missed. This time he threw a wrench and a tool box, the only weapons on board, at the men on the deck of the submarine. It is not recorded whether or not the tools found their mark.

Kapitän Feldt, the luckiest U-boat commander in all of the German Imperial Navy, decided against further risk. He ordered the crew into their hatches, halted the diesels, and instructed the helmsman to dive. As the last officer battened the hatch in the conning tower closed, U-156 slipped nearly noiselessly beneath the surface of the Atlantic.

The only attack on the territory of the United States during World War One was now ended.

Although damaged, the tugboat Perth Amboy did not sink, and its injured crewmen were rowed ashore. All survived their wounds.

Alerted to the hour-long bombardment, nearby residents swarmed the bluffs of Nauset Beach to view the craters created by the errant German gunnery. Within days, reporters arrived to interview survivors of the attack. Captain Tapley said, “I never saw a more glaring example of rotten marksmanship.”

In the follow-up, the Secretary of the Navy ordered the Ordnance Department to determine why the Mark IV bombs failed to detonate. Ultimately, all Mark IV bombs in service were replaced with improved designs.

Thanks

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!